Exhibition VI

Peter Halley: Direction

Millennia ago in Mecca, the icon was rejected and idols broken. Al-Kaaba (Arabic for ‘The Cube’) was constructed by Prophet Abraham (PBUH) and later rebuilt by the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH). The heart of the universe and locus toward which Muslim prayer is directed, the Kaaba symbolically unifies Believers under the Law of God. This primordially simple shape serves as man’s first monument of conceptual art. Collapsing the earthly and the sublime, the cube extends the horizontal lines of the straight path through life upward into the vertical planes of spiritual transcendence.

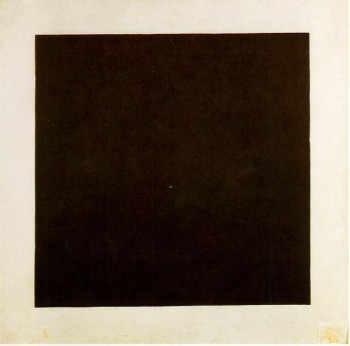

Centuries later in Europe, the Florentine artist, Giotto, emptied images of the iconic value they held in Byzantine art to father the Renaissance. In turn, in the twentieth century Kazimir Malevich reduced the image to a minimalist gesture, fashioning a secular icon in his painting, Black Square (1913).

Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross, 14 panels of abstract art retelling Christ’s Passion,1958-66

Time and time again, humanity would turn to an abstract object in an attempt at ethical resolution: amidst the tyranny of the First World War, Malevich’s monochromatic masterpiece; and after the second, Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross (1958-66). Malevich created a work profound with the force of its tension: a congruence of opposites, it weds omnipresence and total void, beginning and end. Newman too employed black—the color that is at once everything and nothing—in responding to what he called a “moral crisis,” the question of what to paint in the wake of carnage. His answer was to offer runs of darkness contrasted against paled hues.

Direction, an exhibition at Mottahedan Projects opening in February 2013, presents Peter Halley’s new series, centered on the architecture of the Kaaba. Fortuitously, 2013 serves as one century past the date Malevich ascribed to Black Square. The spiral-like nature of history is further revealed when the works are set against the backdrop of bloodshed issuing from war and revolutions in both East and West today.

When confronting these images, the viewer is called upon to declare his/her stance vis-à-vis the subject. In a world in which consumer choices increasingly define the self, these works demand a different type of individuation, that of belief. The status of the work changes in accordance with the viewer’s decision(s). The abstract geometric forms take shape within the context of each individual history, meaning something different to each viewer at each moment. Caught in the constant swing of the pendulum of significance, the works participate in a Saussurian semiotic system that takes for granted the arbitrariness of the sign. Halley thus continues the work he started in the 1980’s alongside theoreticians like Barthes, extending semiotics to the quotidian sphere. His works are the product of a closed set of geometric forms whose language is manipulated to form statements (i.e., paintings) informed by evolving psychological and cultural influences.

To use Neo-Kantian thinker Herman Cohen’s formulation, which expressed aesthetic judgment in terms of the ‘pure feeling’ produced by the work independent of thinking and willing, Halley’s works simultaneously impress and discomfit the viewer, soliciting a reaction even before they have been intellectually understood. The paintings’ straight lines and basic geometry are at once alienating and inviting, beautiful and naïve. Just as Halley previously demonstrated that neither geometry nor technology function as innocent forces in Western society and philosophy, in Directions, he thus suggests that even the transcendental is filtered through discourses of dominance.

Inverting the process of discovery in his previous work, which often exposed realities about the social body, Halley here illustrates the external organization of belief in order to uncover the perplexing and problematic nature of our most fundamental beliefs about the soul. These paintings are all surface—they show an exterior wall and door—and yet their true subject is the spiritual expanse that lies beyond that shell. In an application of anthropic mechanism, which asserts that the organic can be described in mechanical terms, Hallley’s automatist style paintings in this series stand as a metaphor for the modern individual. The creation and viewing of these works is rendered a self-reflexive act for the artist and audience, respectively. With the doorway figuring as the heart of the work, the painting is reformulated not as the presentation of an architectural form but as a representation of the self.

These works are beguiling. Touches of Day-Glo colors among a predominantly subdued palette of gray and muted black lend a luminosity reminiscent of the spirituality they symbolize but with a brightness that somehow clings hollow. Following in the footsteps of predecessors like Andy Warhol, Halley utilizes a style that appears supremely doable. Nevertheless, even as the artist blurs the line between himself and the viewer, the philosopher and the common man, the works are hieroglyphic to those unfamiliar with the theory and politics in which they are embedded. In a self-conscious performance, Halley’s paintings engage in the inaccessibility they criticize. They entrap us as they liberate us, cynically intimating that we cannot live outside the boxes of control while optimistically providing us with the tools to break free.

In this latest iteration in an oeuvre based on exposing the underlying structures and limitations imposed by our modern world, Halley continues to ground his practice on a principle expressed by the artist Carl Andre: that in the short span of our lives, accomplishing one task is enough. Rather than a means of connecting individuals as in his previous works, the conduit is refigured in the current series as representative of a transcendental relationship. Providing a foundational standard around which the work is structured, the conduit also symbolizes the direction to which a life might be devoted—the right path stretching beyond the doorway to emancipation.

Peter Halley was born in New York City. He received his BA from Yale University and his MFA from the University of New Orleans in 1978, remaining in New Orleans until 1980. Since 1980, Halley has lived and worked in New York. Halley has had one-person museum exhibitions at the capc Musee d’Art Contemporain, Bordeaux (1991), the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid (1992), the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1992), the Des Moines Art Center (1992), the Dallas Museum of Art (1995), the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1997), the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art (1998), the Museum Folkwang, Essen (1998), and the Butler Institute of American Art (1999). His work has been exhibited in Mary Boone gallery, New York, Waddington-Custot Gallery, London, Thaddeus Ropac gallery, Paris, and Mottahedan Projects, Dubai.